Transhumanism is the great merger of humankind with the Machine. At this stage in history, it consists of billions using smartphones. Going forward, we’ll be hardwiring our brains to artificial intelligence systems. Transhumanists are always talking about the smartphone-to-implant progression—and so am I, but for very different reasons. Running parallel to this deranged effort is genetic engineering. Instead of getting an mRNA shot that produces reams of synthetic protein, you’ll get custom shots to upgrade your DNA. It’s like a face lift for your cellular nuclei. That’s another progression they can’t stop talking about—and neither can I.

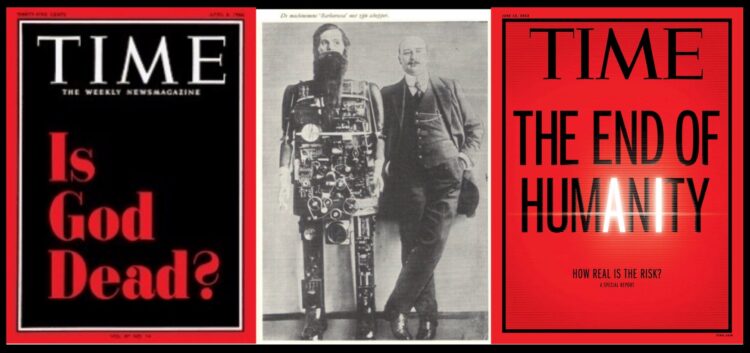

In posthuman versions, it all culminates with the bits and bytes of your personality being digitized and transferred to an e-ghost who goes on evolving in endless virtual space, even after your body dies. Somewhere along the way, they foresee some genius inventing a "godlike” artificial intelligence who assumes the role of a God they believe never existed. Ultimately, transhumanism is a spiritual orientation—not toward the transcendent Creator, but rather toward the created Machine. Think of it as a Disneyland ride where instead of praying for it to end, you pray to the animatronic muppets chattering around you in the hopes of becoming one of them.

My professional life was spent touring with the music Machine. The first few concert tours were around the US. By the time the pandemic shut down our jobs, I’d been all over the world. Some call me Joebot—others call me Joe Rigger. The term "roadie” is politically incorrect, so don’t go there. As a house rigger, you climb high steel to hang the suspension system’s motors. You walk beams a hundred feet in the air and climb angle iron like an ape. As a tour rigger, you travel with the Machine from arena to arena, directing one team of army ants on the floor and another team of high steel apes overhead. The primary goal is to hang forty-plus tons of lights, sound, video, and automation, and ensure nothing falls down, especially not you. I learned a lot about engineering safety. I learned more about social psychology. And I learned even more about social engineering.

Up above are the stage lights. Down below are what Sigmund Freud would call "prosthetic gods.” These are tiny mortals transformed by technology. The same sensory Machine will turn various starving artists into rock stars, rap stars, country stars, cyborg stars, cagefighting stars, political stars, slutpop starlets, or superstar televangelists. Entertainment technology is not "neutral.” No technology ever is. Lights, sound, and video have certain tendencies and embedded values, a limited range of possibilities, out of which comes a deep transformation—not only of the stars themselves, but of the crowds on the arena floor. Mass entertainment is a seductive form of social engineering. The arena is a thundering temple of the Future™.

From the beginning, the Machine and I have had a love/hate relationship. Its intricacies are mesmerizing. And that’s the problem.

"Open the temple door, HAL”

So long as we’re telling stories here, you should know my academic life was spent studying religion and science—the latter being the fastest growing world religion. Two experiences really hit me. There’s a legendary medical facility at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville called "the body farm.” In one of my undergrad science labs, we visited the facility to inspect a cadaver. It had been there since the nineties, so the man’s bones were yellow and his skin looked like beef jerky. I’d been reading books on transhumanism, so the first thing I noticed was the steel plate screwed onto his skull, the primitive pacemaker attached to his heart, and the metal hinge that had replaced his knee. In life, the man had been a cyborg pioneer. His withered ghost still haunts my mind, some twenty years later.

In 2015, I moved from Portland, Ore. to pursue a graduate degree at Boston University. Their School of Theology has a specialized track dedicated to the scientific study of religion. My adviser was Wesley Wildman, a genius mathematician turned unorthodox theologian. Soon after my arrival, he founded the Center for Mind and Culture (CMAC), a multi-million dollar think tank in Kenmore Square. Appropriately, it’s just around the corner from the Lourdes Chapel and across the way from the WHOOP Unite wearable biosensor company. It sits at the intersection of healing and enhancement. Among the many projects then conducted at CMAC was the agent-based simulation of religious social systems. Imagine the video game SimCity with a million psychologically complex characters powered by artificial intelligence. If you let your profane imagination go wild, you can see these bots praying to their creator. In base reality, that would be the programmers and designers.

One of CMAC’s visiting fellows was Justin Lane, an AI expert who was finishing his PhD at Oxford. He became my close friend and mentor. Everything I know about the nuts and bolts of artificial intelligence began with him. Anything stupid I write from here on is not his fault.

Much of my on-foot research in Boston was conducted at a Latin Mass cathedral, a Sikh gurdwara, and Harvard’s Museum of Natural History. My thesis fieldwork centered on various locations run by L’Arche, a Catholic organization whose caregivers live with people suffering from intellectual disabilities. But I also spent a fair amount of time at the Center for Mind and Culture, trying to understand what my egghead colleagues were up to. They had a massive computer system in a storage closet. Its server racks hummed as the AIs trained on vast amounts of social, psychological, biological, and religious data. For big projects, the center also had a direct transatlantic connection to a supercomputer housed at Oxford. The purpose is to model religious behavior in order to test scientific theories and use that information to craft more effective public policy.

CMAC’s simulation projects range from religious terrorism to public health, particularly vaccine uptake. The entire premise troubled me then, as it troubles me now. Every one of the scientists, programmers, and scholars working on these projects is a good person. They’re advancing their own careers, sure, but their primary motivation is to make the world a better place. Of that, I am absolutely certain. Therein lies the paradox. As with the scientific study of religion itself—which seeks to quantify the human soul and calculate its mysteries—modeling religion in silico is a blasphemous attempt to capture the Spirit in the Machine. It’s also considerably useful.

My biases are what they are, but that paradox of good people constructing a digital abomination didn’t sit right. It kept nagging me, even after I left academia to do more arena tours overseas. Beginning with a circle around the US, we worked our way from Europe and Oceania over to Thailand and Indonesia. I spent my down time in Christian cathedrals, Buddhist and Hindu temples, and Islamic mosques. My last night in Jakarta, I stumbled into a random hostel and wound up sleeping in some kind of low-rent plastic space pod with sickly blue lights and a sliding bay door. Things only got weirder from there. Let me tell you one more story.

A Rigger on the War Room

When the Covid panic broke out, I was living in Great Barrington, Mass. It’s a quiet town in the Berkshires filled with ski bunnies, cosmopolitan transplants, and vaccine-hesitant Anthroposophists. To my chagrin, the plague masks were pulled on one by one. The concert industry was vaporized in a flash, taking my livelihood with it. On television, my then-girlfriend and I witnessed the narrative shift from "It’s racist to avoid Chinatown” to "If we can save just one life.” Houses of worship were shuttered. Spy drones were deployed over US cities to police social distancing. Contact-tracing apps were used to track people’s movements. Bill Gates issued directives on cable news, smirking in that stupid sweater. As the novelist Philip K. Dick might say, the Black Iron Prison had closed its gates.

One night, my close friend—known only as the Deerhunter—insisted I watch an uncut PBS interview. For two hours, I listened to Steve Bannon explain the crisis of the West to Michael Kirk. It was like watching Hermes dance on the head of a dumbfounded temple magician. It was absolutely brilliant. My next thought was I had to get a hold of this guy. Surely, he could tell me how a bad flu had made the whole world lose its ever-loving mind. But you don’t just look up Stephen K. Bannon in the phone book. The internet was no help, either. He had a new show about war or something, but there was no contact info on the website. I considered taking in an episode or two, but I’ve never had a taste for politics.

So I put Bannon out of my mind, and went back to watching America descend into Chinese-style technocracy. I packed up a survival bunker on wheels and started moving cross-country, bearing witness to my nation’s descent into mask fights and race riots. Little did I know, I’d sent a psychic signal out into the ether. Something like that, anyway. The universe is a strange place.

Exactly one year later, March 2021, I saw a broadcast of Bannon’s War Room: Pandemic for the first time. The reason was that out of the blue, their producer had invited me on to discuss transhumanism. To my amazement, Steve had read my article on digital immortality at The Federalist. It was part of my ongoing series about technology. Unlike most conservatives, or most people in general, Steve could see techno-dystopia looming on the horizon. Even his detractors revere his preternatural gift for spotting tectonic cultural shifts. Due to a momentary lapse of judgment, he saw something in me, too. That fateful War Room appearance was my first time ever on air, and honestly, it was maybe the third or fourth time I’d ever used Skype. At that point, I’d even scrapped my smartphone.

Two days later, Bannon asked me if I’d like to come on full time to cover transhumanism. I asked him to give me a week to think about it. The concert industry appeared to be opening up, and for me, that’s where the real money was. I composed a draft email to one of my old production managers. To my surprise, he suddenly emailed me before I ever hit send. We hadn’t spoken in a year. It seemed like an omen. He offered me a spot as head rigger for a tour scheduled for Europe and Israel, then back for a loop around the US and Canada. Therefore, I would need to get the vaxx. There were ways around it, of course, but recent headlines indicated stiff fines and possible jail time.

My decision was basically made for me by another strange coincidence two days later.

By that time, I was living in a tiny apartment in Missoula, Montana, waiting for the world to thaw out. My next door neighbor was an eccentric German biologist who worked in a lab at the local university. After six months of casual banter, usually about his fieldwork in nearby forests, we finally went out for coffee to have a real discussion about his work. I listened in abject horror as he told me about the biodigital experiments his team was conducting on animals. They had fitted various insects with electrodes to make flying remote-controlled zombies. Far worse, they had implanted brain chips into a few deer for the same purpose. It wasn’t a foolproof mechanism, but he was able to stimulate them to turn left or right, and stop in their tracks.

This sort of thing has been done for decades, going back to the famous bulls implanted by Jose Delgado, but I’d never met anyone who actually worked on it. My neighbor’s next career move, he hoped, was to move on to human subjects. His lab’s data was already being sold to the brain chip company Blackrock Neurotech, and he had recently pitched a contract to Neuralink. My untouched coffee sat there getting cold.

As our conversation meandered, the topic turned to toxic university speech codes and the stifling effect of political correctness. Or rather, that was my take on the matter. He was all for it. Despite his conviction that climate change meant humanity wouldn’t survive another two hundred years, he was certain that we’d soon do away with racism, sexism, and homophobia. Although an atheist, he was from a Muslim background, so the Israel-Palestine situation really got his blood boiling. When I pointed out that world peace won’t matter if we all go extinct, he just shrugged. It was as if he’d never considered it and had no interest in doing so now. Rolling my eyes, I argued that human beings are instinctively tribal. Global homogeneity a silly pipe dream. He looked at me with a sheepish grin. "One day, we may use our implants for this.”

That night, I called Bannon to take the job. I’ve never been more certain about a decision in my life, and I have never looked back.

It’s 2023 now and things are moving fast. If tech accelerationists have their way, everything we know and love will be broken. It’s their dream versus ours. Speaking of, I’ve been having the damnedest dreams lately. Most of this book was written in an attic above a piano-playing Anthroposophist, and I swear, there’s some kind of juju in the air. This is what I jotted down:

I’m climbing a giant tree, careful to avoid the highest branches. They look flimsy. A group of children is climbing up behind me. Suddenly, a gigantic Elon Musk climbs over me, smiling and laughing. He goes straight for the most precarious limb. As the children cheer, the entire tree shudders. It’s about to topple over and take us all down.

There are multiple ways to interpret any dream. To me, it is either a projection of your hopes, a projection of your fears, a lot of random noise, or a clear, albeit symbolic signal of actual realities in the past, present, or future. Many dreams contain all four blended together. A fellow rigger would probably say this dream was an expression of me being a weak ass climber. To which I would say, try me. A transhumanist might say the same, but my response would be more introspective. I have my own interpretation, as do you by now.

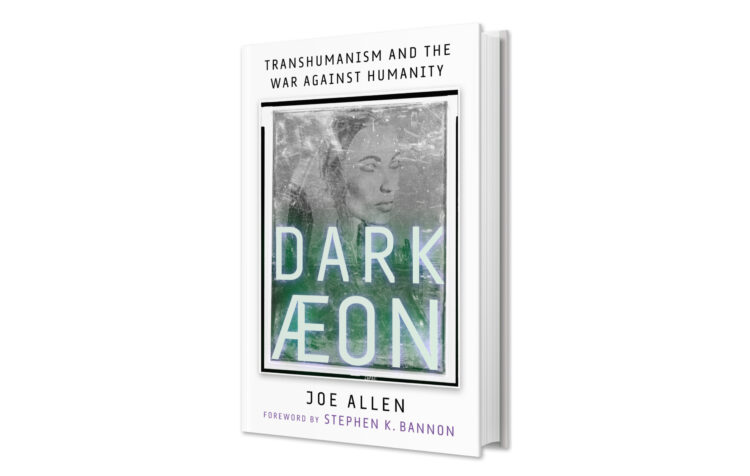

This is a book about dreams of the future. It’s a map of ethereal worlds where humans are destined to become god-like immortals and summon far greater gods through the Machine, tempting the possibility of human extinction. Each one is based in actual science and nascent technology, yet all of them strain the limits of credulity. Every reader will have their own interpretation. Some will see the inevitable. Others will scoff at such delusions of grandeur. Neither are assured. Our future is still wide open. But you don’t need a coat of many colors to know that, should any of these dreams come true, humanity is hurtling into a dark aeon.

Powerful people are prepared to chase these dreams at our expense. Knowing this, we must make our own plans.

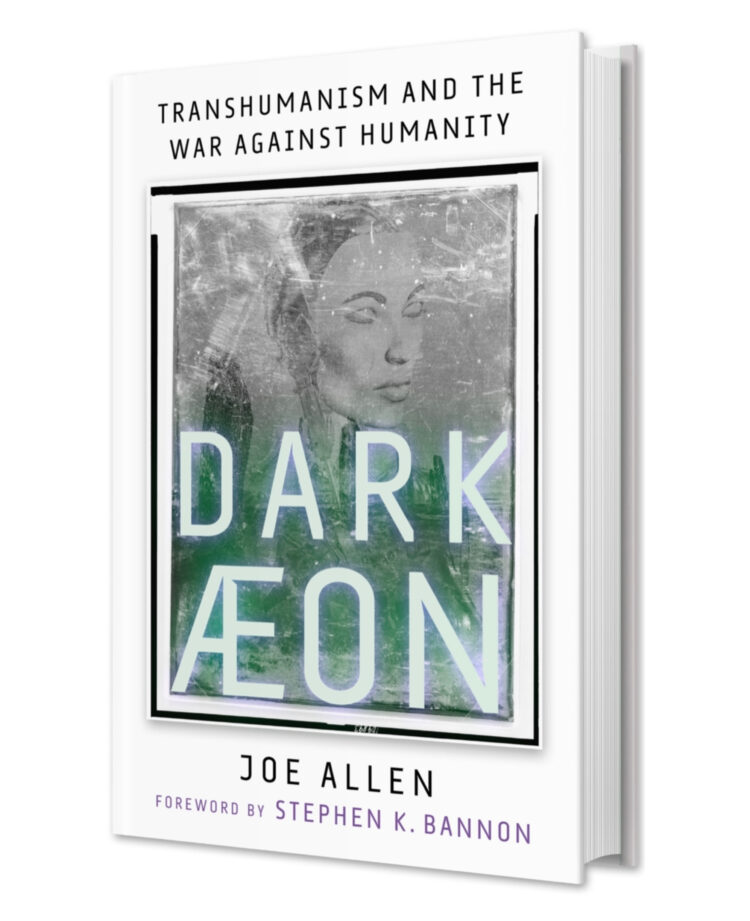

DARK ÆON is now for sale here (Amazon), here (Barnes & Noble), or here (BookShop)

SOLD By this below! QUOTE

GAIL / @joythatlasts

Stephen K Bannon’s War Room

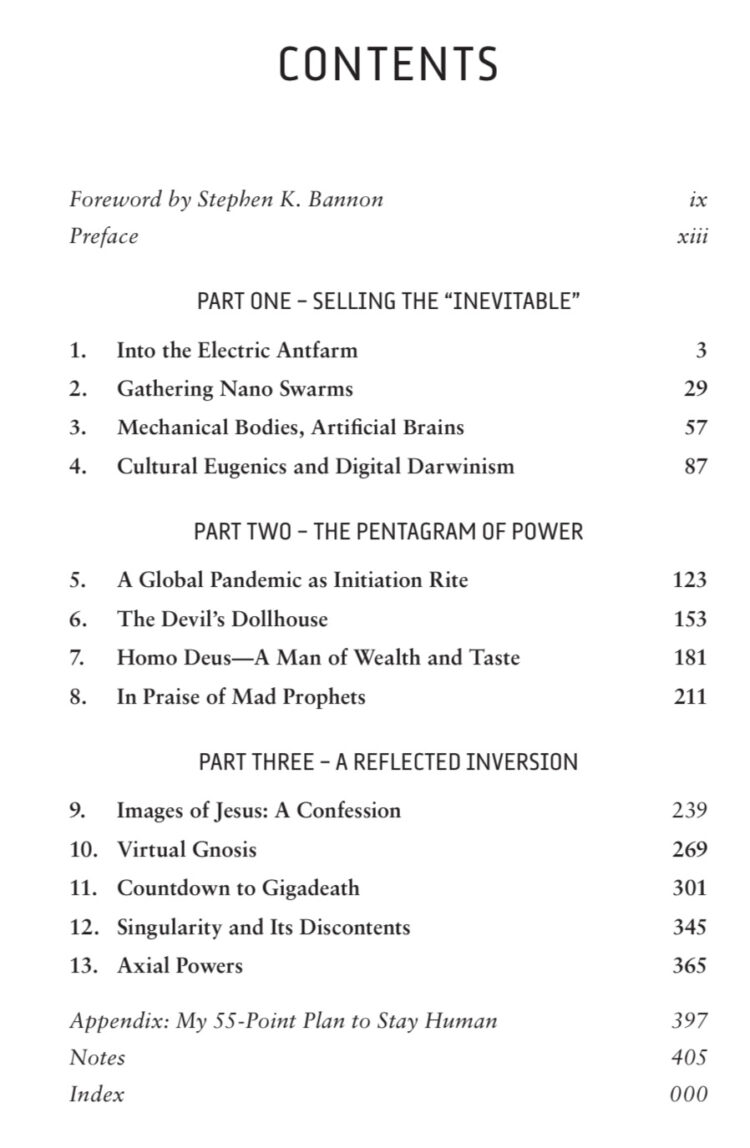

DARK ÆON — Preface (and Table of Contents)

How it started

Joe Allen by Joe Allen August 31, 2023 Reading Time: 10 mins read

Home Newsroom

“Transhumanism is the great merger of humankind with the Machine. At this stage in history, it consists of billions using smartphones. Going forward, we’ll be hardwiring our brains to artificial intelligence systems. Transhumanists are always talking about the smartphone-to-implant progression—and so am I, but for very different reasons. Running parallel to this deranged effort is genetic engineering. Instead of getting an mRNA shot that produces reams of synthetic protein, you’ll get custom shots to upgrade your DNA. It’s like a face lift for your cellular nuclei. That’s another progression they can’t stop talking about—and neither can I.

In posthuman versions, it all culminates with the bits and bytes of your personality being digitized and transferred to an e-ghost who goes on evolving in endless virtual space, even after your body dies. Somewhere along the way, they foresee some genius inventing a “godlike” artificial intelligence who assumes the role of a God they believe never existed. Ultimately, transhumanism is a spiritual orientation—not toward the transcendent Creator, but rather toward the created Machine. Think of it as a Disneyland ride where instead of praying for it to end, you pray to the animatronic muppets chattering around you in the hopes of becoming one of them.

My professional life was spent touring with the music Machine. The first few concert tours were around the US. By the time the pandemic shut down our jobs, I’d been all over the world. Some call me Joebot—others call me Joe Rigger. The term “roadie” is politically incorrect, so don’t go there. As a house rigger, you climb high steel to hang the suspension system’s motors. You walk beams a hundred feet in the air and climb angle iron like an ape. As a tour rigger, you travel with the Machine from arena to arena, directing one team of army ants on the floor and another team of high steel apes overhead. The primary goal is to hang forty-plus tons of lights, sound, video, and automation, and ensure nothing falls down, especially not you. I learned a lot about engineering safety. I learned more about social psychology. And I learned even more about social engineering.

Up above are the stage lights. Down below are what Sigmund Freud would call “prosthetic gods.” These are tiny mortals transformed by technology. The same sensory Machine will turn various starving artists into rock stars, rap stars, country stars, cyborg stars, cagefighting stars, political stars, slutpop starlets, or superstar televangelists. Entertainment technology is not “neutral.” No technology ever is. Lights, sound, and video have certain tendencies and embedded values, a limited range of possibilities, out of which comes a deep transformation—not only of the stars themselves, but of the crowds on the arena floor. Mass entertainment is a seductive form of social engineering. The arena is a thundering temple of the Future™.

From the beginning, the Machine and I have had a love/hate relationship. Its intricacies are mesmerizing. And that’s the problem.”

*The above Drew ME Right In.*

Just ordered the book…

The TREE DREAM: The Tree of Life, Freedom, Humanity is unstable… the children represent new generations coming up from the foot of the tree that Joe struggles to protect. Giant Elon Musk (Fee Fi Foe Fum) overpowers the Tree representing the source of techno-trans-humanism. The far reaching branches will not support the unnatural weight of Godless bio-techo-theurgy. Joe is tasked to inform the children to keep the tree alive. Humanity will be saved by accepting and yielding to the Grace and Glory of God.

I’m inclined to purchase the book simply because you quoted Philip K. Dick. I was very young at the time and understood maybe a third of the conversation when I was fortunate enough to have a conversation with him a year before his death. Despite Hollywood leaching off his books and short stories he was nearly destitute. One of your chapters seems to focus on “Homo Deus”, a book by Yuval Herari. That book was barely worth the time required for the read.

As to “Transhumanism”, Humans have been augmenting themselves physically for more than 20,000 years. Reshaping the human body into shapes we would consider “grotesque” or “inhuman”. Is that something covered in the book?