People talk about brain implants as if they're an imagined biohorror in the distant future. This is a misconception. Hardwired trodes already exist, they're more widespread than you think, and they'll only be more prevalent as time goes on.

Today, it's an iPhone 14 under the Xmas tree. Come the Singularity, transhumanists hope and pray, it'll be an iTrode 666 in your cerebral cortex.

Synchron and Blackrock Neurotech, alongside numerous labs funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), are at the forefront of this human experimentation.

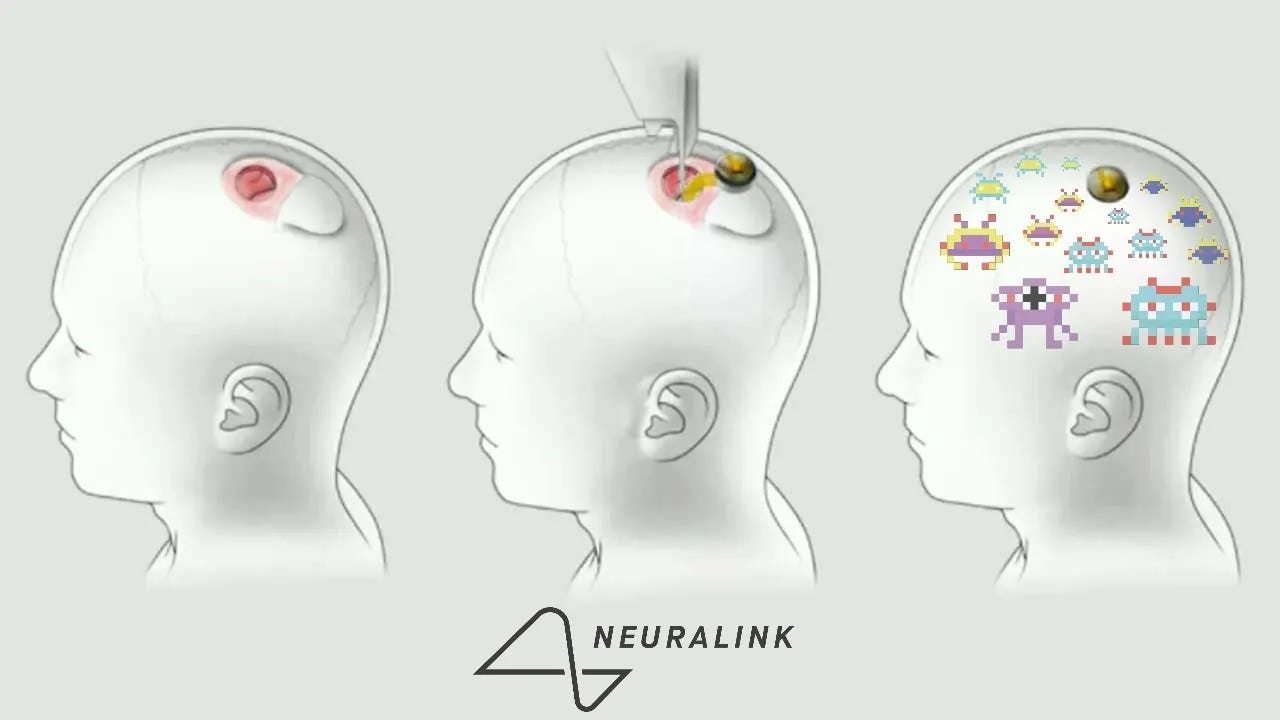

Neuralink is racing to catch up—burning through lab animals like so much kindling—and will likely take the lead once they're approved for human trials.

Currently, a brain-computer interface (BCI) can provide quadriplegics and locked-in stroke victims a superior hands-free experience. Patients can move cursors onscreen. They can type text with only their thoughts. They can operate robotic arms to move beer bottles to their lips. The late Matthew Nagle, who received the first proper BCI in 2006, was able to play Pong "telepathically."

Enjoying a decent head start, Blackrock Neurotech is the most prolific brain-jack racket. "36 people around the world have an implanted brain-computer interface," their website states. "32 of them use Blackrock technology." (If I had to wager, the former number is likely greater.)

These silicon seeds have been planted in a bed of gray matter, and after recent rounds of generous financing, they're growing fast.

It's important to note, though, that current BCIs are used to read the neurons, not write onto them. At least for now. Yes, there are deep brain stimulation implants—wired electrodes that sit under the skull, typically used to control tremors, and more recently, to alter mood. These simple systems, embedded in over 160,000 heads around the world, do provide input signals. But that's a long way from hearing articulate voices in your head.

However, should the most aggressive developers realize their dreams, readily available BCI systems will read and rewrite our minds like RAM drives. In the near future, we're told, commercial implants will allow regular humans to commune with artificial intelligence as if we were spirit mediums drawing ghosts out of the aether.

Manufacturers shield themselves from public outcry by promising the lame will walk and the blind will see. That's already happening, but the openly declared goal is to move from healing to enhancement.

Last week, Synchron had their BCI bankrolled by the palm-scanning home-invader Jeff Bezos and the island-hopping "Vaxx King" Bill Gates, with $75 million in total investment. Currently, the Brooklyn-based company has jammed chips into multiple human brains. Last summer, they received FDA approval to start trials in the US. Like most BCIs, the device functions like a telepathic touchpad in your skull.

Synchron's main product, the Stentrode, is much less invasive than its competitors. For instance, Blackrock Neurotech uses a micro-electrode array that sits on top of the brain, requiring doctors to cut through bone for installation. Neuralink's processor is basically a quarter-sized skull plug, with 1,024 hair-thin wires fanning out like jellyfish tentacles into the gray matter below.

The Stentrode is just a wire-mesh stint, like a tiny pair of Chinese finger cuffs. Surgeons insert this stint in the jugular vein and maneuver it up through the brain's blood vessels to the desired location. Once installed, the Stentrode monitors brain activity for intention. This information is sent down a cable to an antenna device sitting on the chest under the skin. That data is then transmitted to external devices.

Like its competitors, Synchron's current projects are focused on the motor cortex. In a series of exercises, the user concentrates on a specific intention. The device then reads the corresponding brain activity, and external artificial intelligence systems create a digital mirror, correlating the brain pattern to the intention. All of this happens in microseconds, allowing for real-time monitoring.

After the brain's partial mirror image is fleshed out, the paralyzed user can do things like move a cursor onscreen to type text. Synchron's most famous patient, a locked-in ALS victim, made headlines in December of 2021 for sending the first telepathic tweet. Using the Twitter account of CEO Tom Oxley, he typed out:

And in a follow-up tweet:

my hope is that I'm paving the way for people to tweet through thoughts

Only a monster would deny the obvious benefit of inserting a BCI into a fully conscious but uncommunicative vegetable, allowing him to speak to his loved ones once again. The snag is that brain-computer interfaces won't stop here. The ultimate goal is cyborg supremacy.

"Synchron's north star is to achieve whole-brain data transfer," Oxley said last year, evoking a kinder, gentler version of the Moravec Transfer. "The blood vessels provide surgery-free access to all regions of the brain, and at scale." This means doctors will eventually snake Stentrodes into every lobe and cortex—sort of like having an Alexa in every room of your house—and subsequently create a digital twin of the organ in silico.

It's the ultimate fusion of mind with machine, allowing the user to control digital activity with his thoughts alone. In turn, this gives scientists and artificial intelligence total access to the user's mental gears. Because most primary functions are nearly identical from person to person, once you've mapped one brain, you've basically mapped them all.

For many working on BCIs, the prospect of a man-machine merger is intoxicating. Possessed by the same spirit as Neuralink's owner Elon Musk—who openly states his desire to merge brains with AI for intellectual enhancement—Synchron's Tom Oxley has a more heart-warming vision of our cyborg destiny:

In the future, I'm really excited about the breakthroughs BCI could deliver to other conditions like epilepsy, depression, and dementia. But beyond that, what is this going to mean for humanity?

What's really got me thinking is the future of communication.

Take emotion. Have you ever considered how hard it is to express how you feel? You have to self-reflect, package the emotion into words, and then use the muscles of your mouth to speak those words. But you really just want someone to know how you feel. …

So what if rather than using your words, you could throw your emotions? … At that moment, we would have realized that the necessary use of words to express our current state of being was always going to fall short. The full potential of the brain would then be unlocked.

Far beyond healing, Oxley wants to transcend the human condition entirely, or at least transform it. In this sense, he's an obvious transhumanist, even if he avoids the term.

This transhuman orientation is shared across the BCI field. As I've covered extensively, various brain researchers affiliated with DARPA, the RAND Corporation, the Royal Society of London, the National Institutes of Health, Silicon Valley, the World Economic Forum, and countless university labs are aiming for an upgraded Humanity 2.0.

I'm not spinning some "conspiracy theory" here. It's simply a thing.

Before Charles Lieber was convicted for taking Chinese money under the table, the Harvard chemist was developing a nanoscale brain-computer interface that could be injected via syringe. This microscopic neural lace merges with the neurons, creating "cyborg tissue" that can communicate with a computer.

"We're trying to blur the distinction between electronic circuits and neural circuits," he told Smithsonian Magazine. And if you browse the names of former Lieber Group members on Harvard's website, it's obvious that Chinese researchers, along with the Chinese Communist Party, share his passion for biodigital convergence.

"This could make some inroads to a brain interface for consumers," a Rice University tech developer commented. "Plugging your computer into your brain becomes a lot more palatable if all you need to do is inject something."

These guys take "the jab" to a whole new level.

Another gross misconception is that transhumanism is a purely leftist or globalist agenda. This may be a politically convenient position to take, but it's indefensible.

Amongst others, the scrappy Silicon Valley investor Peter Thiel is, in effect, a Western nationalist. On the Republican side, he recently funded the senatorial campaigns of J.D. Vance and Blake Masters. On the transhuman side, the multi-billionaire was an initial investor in Neuralink, and is now financing their rivals at Blackrock Neurotech.

Philosophically speaking, Thiel is far more articulate than other tech titans like Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, or the new Conservative, Inc "superhero," Elon Musk. While they share the same interests in life extension, brain interfacing, and artificial intelligence, Thiel explicitly steers his projects toward advancing and defending Western civilization.

For right-wingers opposed to the hubris of transhumanism—an unfashionable term that Thiel wisely distances himself from—his strange blend of traditional mythos and techno-futurism complicates the standard narrative. In a provocative essay at First Things, entitled "Against Edenism," Thiel urges Christians to accept the inevitability, or at least the necessity, of progress. As civilization hurtles toward apocalypse, there can be no return to Eden.

"The future will look very different from the past," he writes, citing Genesis and Revelation. "The Garden of Paradise will culminate in the City of Heaven." In Thiel’s view, the mission to develop technology runs parallel to God's act of creation, which brought order to the face of the deep:

Judeo-Western optimism differs from the atheist optimism of the Enlightenment in the extreme degree to which it believes that the forces of chaos and nature can and will be mastered. The tyranny of Chance will give way to the providence of God.

Exercising our natural human capacities, we are co-creators in this process—aka, Homo Deus:

Science and technology are natural allies to this Judeo-Western optimism, especially if we remain open to an eschatological frame in which God works through us in building the kingdom of heaven today, here on Earth—in which the kingdom of heaven is both a future reality and something partially achievable in the present.

Looking through Thiel's business portfolio—especially Palantir—this "partially achievable" divine kingdom includes wall-to-wall surveillance grids, mass data-mining, military-grade artificial intelligence, BCI control devices, genetic engineering, vampiric blood transfusions from young donors to aging billionaires, and of course, Bitcoin. Lots and lots of Bitcoin.

Call me cynical, but I see little difference between Thiel's technocratic "City of God" and the Beast System of the Antichrist. Even so, there's a quandary that can't be avoided.

No matter how blasphemous his cosmic vision may be, Thiel's argument for the necessity of science and technology is essentially correct. If Western nation-states are to compete, or even survive, in the global Fourth Industrial Revolution—"the fusion of the physical, digital, and biological worlds"—we won't do it with typewriters and sling shots.

We need a plan. And as much as you may despise Thiel's quest for cybernetic Mammon, at least he has one.

We are in the throes of a civilizational transformation. The idea of "progress" may seem absurd when the potholes multiply and basic commodities grow scarce, but technology is progressing nonetheless.

Each of us is being hardwired for control. On the one hand, we're granted control over various devices and vast stretches of virtual space. On the other, elites who deploy those devices and police our virtual spaces are taking control over us.

As the brain-computer interface creeps into public consciousness via news stories and propaganda—as the idea is implanted in our minds—it becomes a profound symbol for total control. With each technical advance, that symbol edges closer to realization.

I'm not saying this to freak you out. Alarmist thinking is weak. But don't tell me "It'll never happen."

The intermediate steps toward this man-machine merger have already been taken. Over the past century and a half, humans have acclimated to the telegraph, the telephone, the radio, the television, and the desktop computer. Now, across the planet, we're fusing with our devices through smartphone-symbiosis.

Holding these screens in our hands, with digital content filling our heads, we already bear a mark that allows us to buy or sell—hovering somewhere between UberEats and the Antichrist. The next phase is a non-invasive BCI skull cap, or brainwave headband, looming just over the horizon. From there, it's a small step to getting an iTrode jammed in your dome.

All of us fall somewhere on the caveman-to-cyborg spectrum, with most sliding rightward on the scale. The question isn't whether society is going there—it's how far each of us will go.

Joe Allen is the transhumanism editor for “War Room.” Follow him at joebot.xyz. or on Twitter: @JOEBOTxyz or Gettr: @JOEBOTxyz.

![‘How Was MAGA Created? Who are the Deplorables?”, Historic Bannon Speeches [Oxford Union]](https://warroom.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Bannon-350x250.jpg)